Vince Staples and the Art of Not Talking

In her 1965 essay On Style, the critic Susan Sontag asserted that, ‘A work of art encountered as a work of art is an experience, not a statement or an answer to a question. Art is not only about something; it is something.’

Throughout the essay, Sontag makes clear her frustration that such an assertion – accompanied by reminders that characters in fictional narrative are not real but part of ‘imaginary landscapes’ – should still need to be made in modern times. Over fifty years later, the West Coast rapper Vince staples seems similarly irked that he should have to make this point and defend his reluctance to justify his work.

In a recent interview with Pitchfork, Staples likens his records to works that, once they are made available to a curious public, are left for the viewer to interpret and assume responsibility for, given the inevitability that ‘everybody’s trying to put themselves in someone else’s picture’.

Staples evidently likes to describe his work as a musician in terms of visual art: ‘I look at an album like an art exhibit, it’s like a solo show […] you put them on the wall, and people gawk at it. That’s the point of an art show. Now, when you see art on the wall, it’s [coming with] two to three things at the most. It has an artist’s name, the name of the piece, when it was created […] Some things have explanation. Most things don’t. So my question would be: Why, in music, is there a need for the artists to explain?’

It seems to be that the pressure to explain and justify one’s work is a problem particular to rappers; if their work references past experiences with violence or drug abuse, they are above all expected to moralise. It’s as if the anxiety persists, thirty years on from the moral panic surrounding N.W.A., that any representation of such experiences without explicit moral judgement by the artist/s themselves equates to glorification.

There’s evidence that this pressure is keenly felt by contemporary rap artists. Even the highly idiosyncratic indie darling Danny Brown, on the final track of his brilliantly experimental 2016 album Atrocity Exhibition, rounds off his narrative of life-threatening excess by proffering the (rather eighteenth-century) caution that, ‘I lived through that shit / So you don’t have to go through it.’ In other words, heed his warning. We can speculate as to whether this eleventh-hour underlining of the album’s moral position by Brown eased critics’ minds enough that it was afforded almost universal acclaim.

It’s arguable that the demand for justification is being made on behalf of the white audiences who, in Staples words, are there to ‘gawk’ at the work of black artists. An apology for the scenes and behaviour depicted in rap lyrics, ideally with assurance that the rapper in question is now adopting a persona that they are now sufficiently distanced from, may be helping to assuage the anxiety of white listeners that their entertainment involves eavesdropping on the culture of an often radically different socio-economic situation.

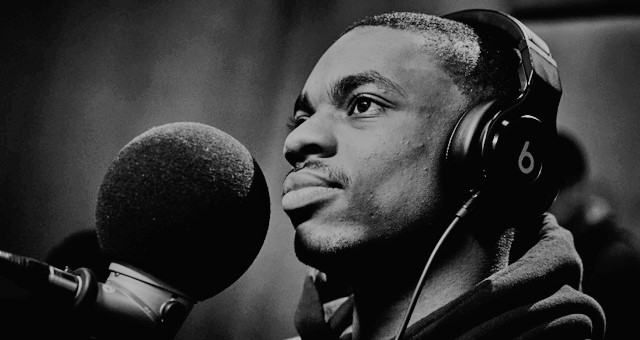

Vince Staples’ lyrics frequently reference a youth spent in the Crips and the experience of growing up in Ramona Park, Long Beach. His debut full-length Summertime ’06 (2015) paired his deadpan yet highly elastic drawl with chilly sonics to create a pervasive sense of unease. In the starkly monochromatic video that accompanied ‘Norf Norf’, Staples is bustled through the various stages of police custody and eventual imprisonment, his alleged crime never alluded to, his unwavering glare his only response to his situation. That aesthetic should have been enough to convey to listeners the complex relationship that Staples has with his past, but still the questions kept coming – in Staples words, usually to the effect of: ‘I heard you just put out an album, but what’s it like to be in a street gang?’

It’s significant that several reviewers approached Summertime ’06 as reportage from a correspondent whose jadedness evidenced a sufficient distance from the experiences that he was relating. Framing the album as an unflinching despatch from somewhere akin to a warzone mitigated against fears of rubbernecking by positioning Staples as a correspondent or chronicler of something that now required the attention of broadsheet-readers.

Following the release of his second full-length, titled Big Fish Theory, Staples is clearly wary of being asked once again to feed interviewers and critics with his assessment of past misdemeanours. Perhaps the anxiety persists around Staples to such an extent because the music itself is so immediately alluring; Summertime ’06 was often stripped-down and snakingly funky, whilst Big Fish Theory finds him embracing danceable house production and paying tribute to Chicago footwork. Above all, Staples flow is effortlessly flexible, stretching and bouncing irresistibly from bar to bar. Sontag reminded her readers that, ‘Art is seduction […] But art cannot seduce without the complicity of the experiencing subject.’ The fear of seduction by a black ex-gang member may be sending critics and audiences scrambling once again for reassurance from Staples that his troubled past, and his current pain, are being explored at a safe critical remove.

It seems that with Big Fish Theory and the surrounding promotional material – including album art, photoshoots, and videos – Staples is attempting to create a coherence of imagery and metaphor that will prove sufficiently self-explanatory that he will finally be left alone. The titular ‘big fish’ is a ubiquitous metaphor for elevated social status, whilst the title of first track ‘Crabs in a Bucket’ makes explicit his concerns with the microcosm of rap fame and the disquieting feeling of being treated a specimen for analysis. Such a strong internal continuity of lyrical metaphor and accompanying visuals – the video for single ‘Big Fish’ simply has Staples delivering his verses from a boat out at sea – has already done much of the interpretative work for his listeners. The imagery is arresting, and the promo material for his ‘Life Aquatic’ tour has been amusing, but one hopes that Staples isn’t being increasingly railroaded into spelling-out or critic-proofing his work.

Despite having created one of the most coherent and distinctive aesthetics in the rap world, it seems as if Tyler, the Creator is next in line to explain himself. With leaked lyrics from his upcoming album Scum Fuck Flower Boy being interpreted as Tyler coming out of the closet, suddenly there’s a renewed expectation for Tyler to justify previous lyrical slurs (including, but not limited to, his use of ‘faggot’) in light of this revelation.

Whilst the use of such insults cannot be condoned, it’s disappointing to see that publications such as High Snobiety have taken such a censorious tone with this story, rather than considering the highly cartoonish, grotesque and highly ironic aesthetic that Tyler has spent years cultivating and placing this new information within the context of an artist who has always tried to provoke. Indeed, the Odd Future collective of which Tyler is the de facto leader is characterised in large part by its queering of hip-hop culture, and includes amongst its members Frank Ocean and Syd the Kid (of The Internet and more recently solo fame). Tyler himself has made repeated references to being closeted and attempting to come out, and perhaps the difficulties of this are represented in the most confrontational and subversive aspects of his work.

Nevertheless, there will likely be a retrospective demand for Tyler to have been a spokesperson rather than simply an artist who makes challenging and often deliberately ugly music. It all speaks of a disquieting demand for black artists to represent as opposed to simply create, a symptom perhaps of an entertainment industry unable to shake the current anxieties around identity politics. Ω