Can we enjoy Qatar 2022? Weighing up the World Cup

The men’s football World Cup Finals are upon us. Which means the most controversially awarded and staged iteration of this sporting spectacle in living memory (even taking into account Russia 2018). The scandals and abuses, the debating points and moral quandaries, have been more multifarious and prominent ahead of this tournament than arguably any other.

As Qatar 2022 commences, we might now be embarking upon the most wide-reaching discourse ever held at any one time about the ethical enjoyment or consumption of a major cultural product. This is likely to be the most covered and commented-upon experience that has ever invited millions of participants to engage with the emotions, aesthetics and pageantry on display all whilst being asked (in some quarters at least) to consider the context and condition of producing the spectacle itself – a collective weighing of human life and value systems against the intoxicating, relentless output of the football entertainment industrial complex. This is the art-and-the-artist debate, the attempt to separate the creation from the creator, playing out on a scale never before seen.

Because football is a game in which aesthetics and artfulness matter. Its individual flourishes and collective patterns differentiate the great players and teams from the also-rans. Its moments of grace, of poise, even of genius, can mean that a single movement or touch of the ball can come to define a tournament or even an entire era.

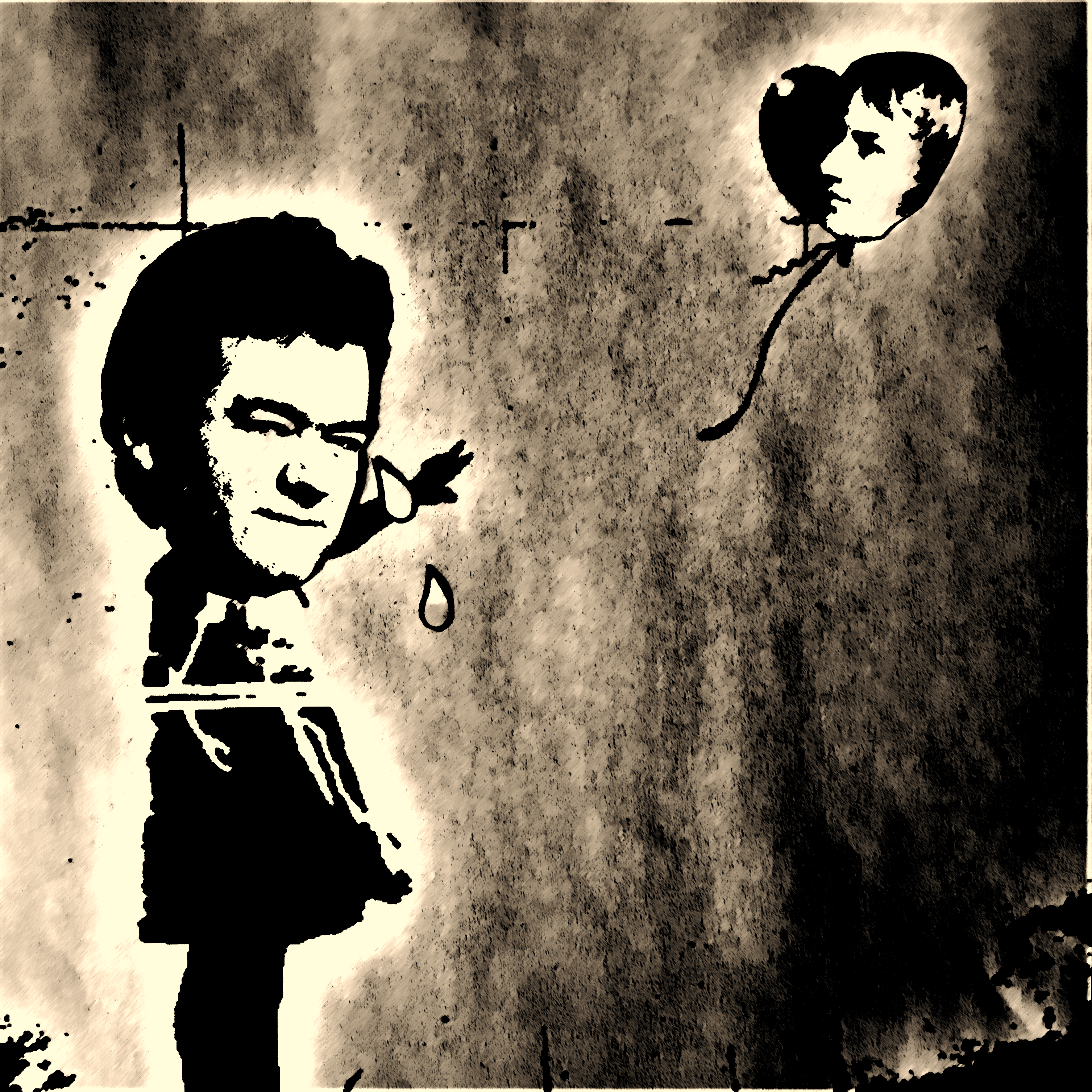

Football is ‘The Beautiful Game’. That beauty is in continual dialectic with the ugly, with the sweaty and snarling exertions of running for kilometres on end and kicking, elbowing, and sometimes biting people. Just as there are ‘sublime’ passes, ‘deft’ touches, and ‘hopeful’ shots from distance, so there are the ‘dark arts’ of tactical fouling, the ‘backwards’ schools of defending and those who seek to ‘spoil’ the game. Pep Guardiola is regarded as a troubled artist and idealist, working in the medium of complex human geometry. Meanwhile, Jose Mourinho is equally celebrated and vilified as an embittered iconoclast who loves only destruction. These are not lofty value judgements espoused only by elitists or academics, but debates held regularly in the public sphere from stadia to pubs to phone-in talk shows.

Aesthetics, and the values attributed to them, genuinely matter in football. Even with the data and metrics available to the game’s commentariat and consumers, helping to drive debates on hundreds of podcasts and YouTube videos and afternoon pub arguments, the ‘eye test’ nevertheless holds at least equal weighting with the numbers. Tottenham Hotspur might sit an admirable fourth in the Premier League table and have topped their group in Europe so far this year, but the unadventurous tactics and visible lethargy of their first half performances have led to outcry amongst fans. Results might be king, but playing in the wrong way – and the moral injury that inflicts – is perhaps the most punishable offence of all.

And beauty can even be leveraged to excuse the inexcusable; Zinedine Zidane may have idiotically cost France the 2006 World Cup by literally headbutting an opponent in the final, but he had scored that otherworldly volley in the 2002 Champions League final, a moment of mental agility and supreme skill by a master of the form. If anything, the headbutt confirmed his rarefied status as a genius and a maverick.

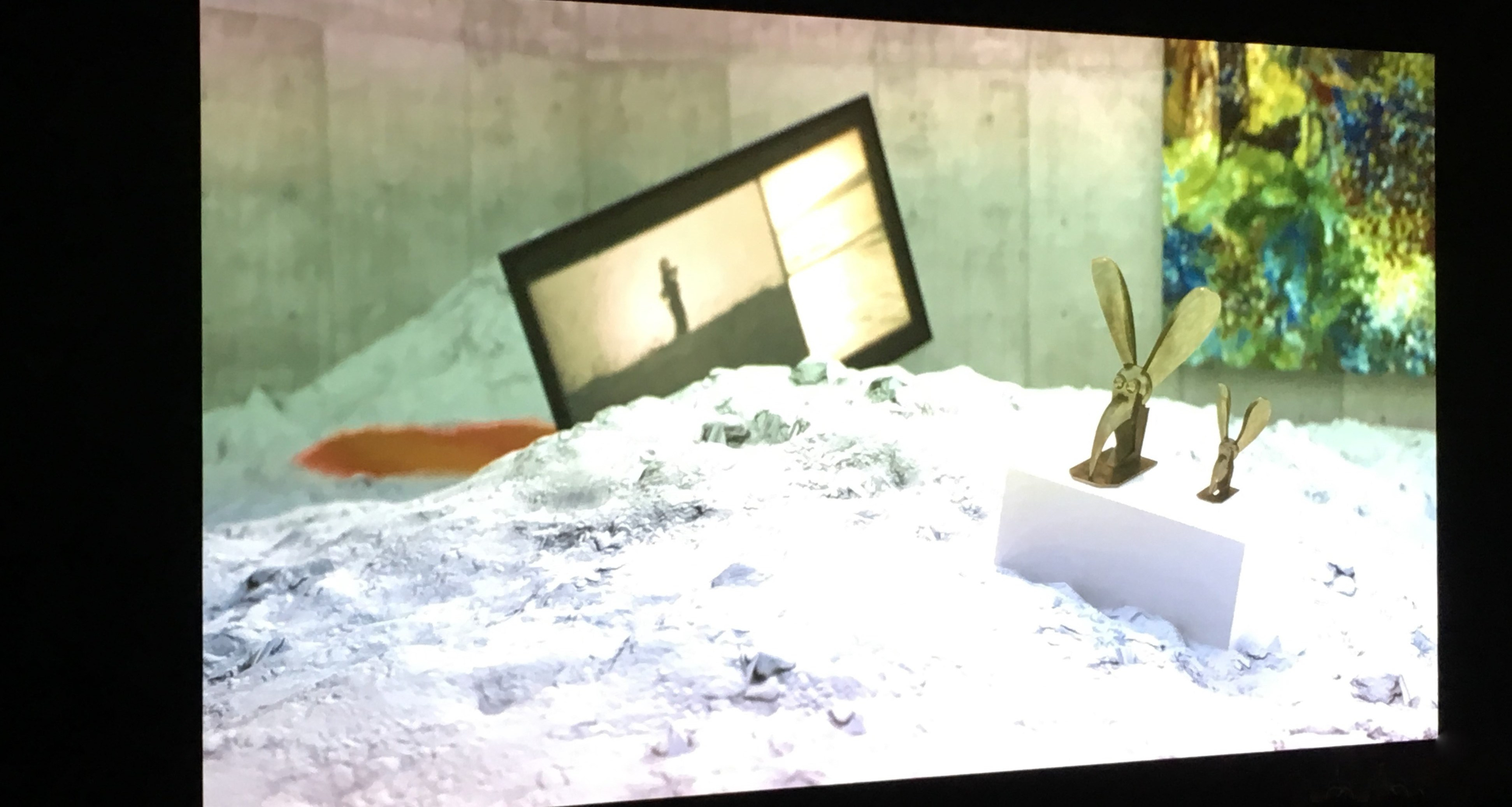

So what of Qatar? The small Gulf state will provide the stage for more moments that will excite, astonish, and appal football fans around the world. On television and in stadia, at least, these finals will look the part, giving us a polished entertainment product played out on manicured grass, under precision lighting, surrounded by giant screens. Yet that same polish, the purpose-built nature of the whole spectacle (given Qatar’s almost non-existent stadium infrastructure beforehand) will draw attention to its gleaming newness and carefully managed, inorganic choreography.

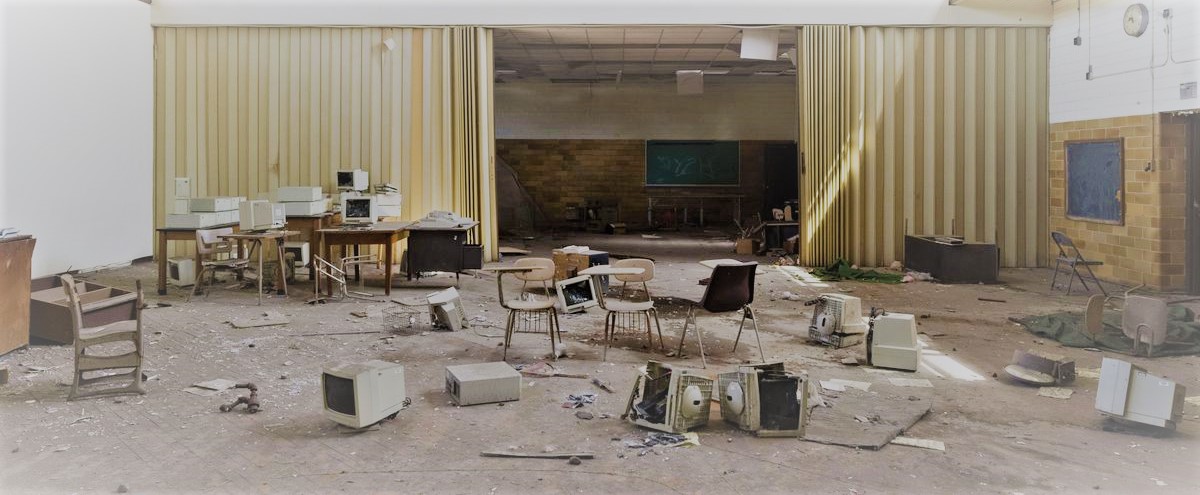

Who designed and built all of this? Who has transformed wide expanses of desert and dust into concourses, fan areas, and luxury hotels?

The answer lies shrouded and buried, known only by migrant workers afraid to speak out. Meanwhile we are asked by politicians and heads of state to look the other way and simply “enjoy the football”. What-about-ism reigns, as we are asked which host nation has ever been truly beyond reproach, as we are told by FIFA top brass that football is a healing force and an agent of progress (even as, they insist, it is still just a sport and certainly not politics, no siree).

The answer is that the spectacle, with all its pageantry and prestige, is more important than the lives and rights of living, breathing people – and all those who have not been so lucky.

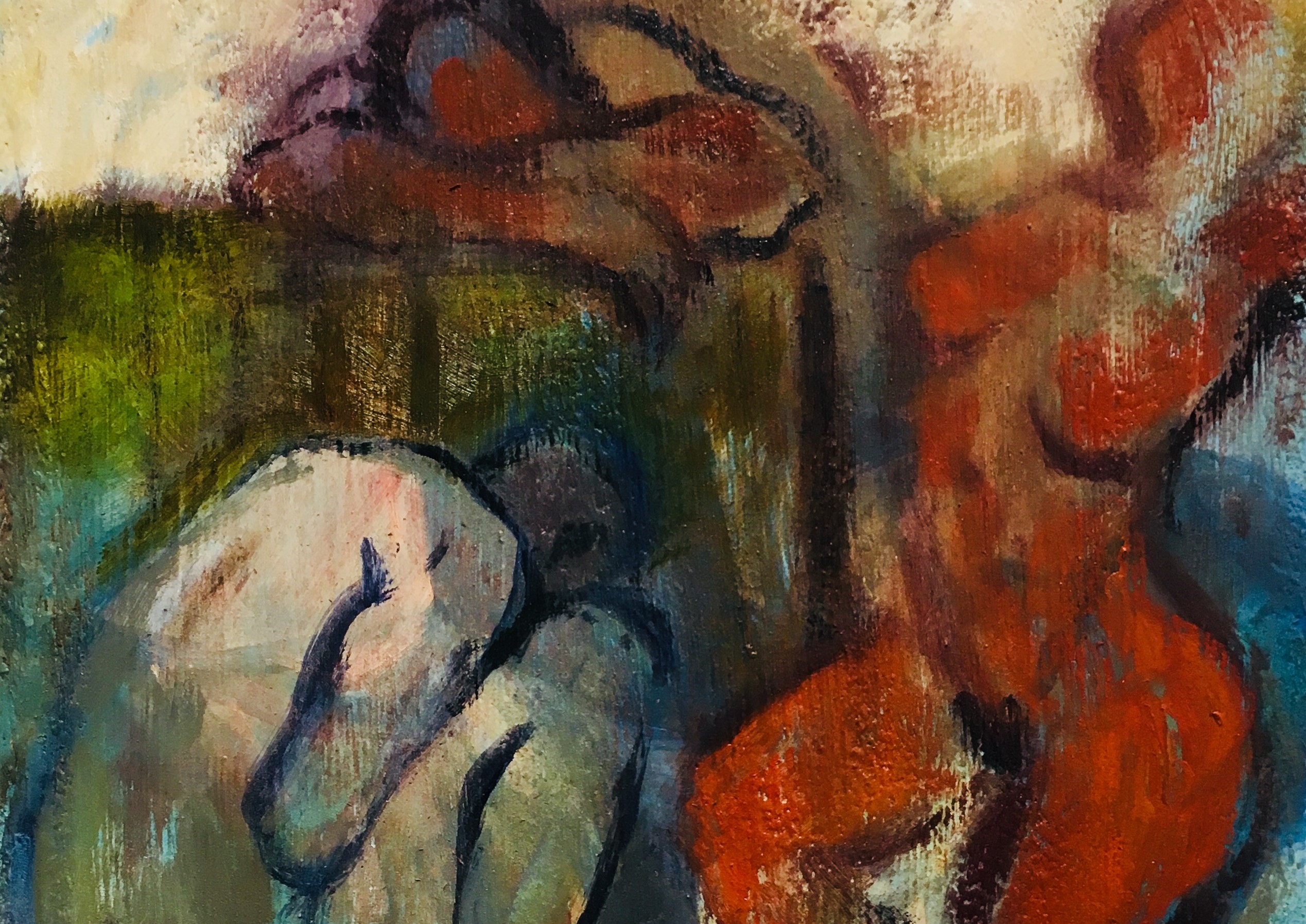

This World Cup, viewed through the knowledge of its human toll, has something in common with the images made by Damien Hirst from the wings of dead butterflies, arranged with an unnerving precision to create something so vivid and precise even as we recoil from the material, deathly cost of its making. Only perhaps it is more obfuscated than that. The human cost of this event is not on display, not laid out in front of the viewer but buried elsewhere, unseen. Rather than being asked to appreciate the full picture and perspective, we are being asked to narrow our view to the length of the pitch. And yet the pristine surfaces and facades of these purpose-built games may well create an eerie spectacle so frictionless, an aesthetic so clean and airbrushed, that some fans and spectators might start to grow uneasy, might start to check the peripheries of their vision to find the scaffolding and seams and inner workings of this tournament.

What might they find? That modern football, in its most elite and rarefied forms, is hugely (and wilfully) compromised by extreme wealth, inequality, and competing geopolitical interests. It is the most popular cultural product in human history, a game about beauty and ugliness, about ecstasy and agony – not only in terms of aesthetics and artfulness, but also in the means of its production and its wielding as an instrument of power. Can the spectacle still be enjoyed in this knowledge? We are about to find out. Ω